No Light Rail in Vancouver!

Debunking Coercion Part 2

Who Put Light Rail in the New Urbanist Platform?

Portland’s well-

Transit’s Anemic Growth

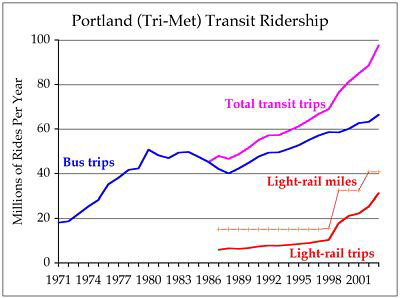

Michael Lewyn’s critique of my paper on Portland reviews Portland’s transit ridership

starting in 1986, the year Portland opened its first light-

The real success story, my paper points out, was from 1970 to 1980, when Portland nearly tripled its transit ridership simply by improving its bus system. The painful transition from bus to rail caused a 10 percent decline in ridership and a 20 percent decline in transit’s share of travel, bottoming out in the year light rail opened. If you begin your analysis after rail construction has literally decimated ridership, it is bound to look good, but if you look deeper you see rail has real problems.

Transit ridership grew after light rail opened, but it grew faster when TriMet was

concentrating on buses and it shrank during the initial light-

Yes, transit ridership has grown since 1986, but it still hasn’t recovered the market share it had in 1980. Then, transit carried well over 2.6 percent of regional travel and 9.8 percent of commuters to work. Today, it carries 2.2 percent of all travel and 7.6 percent of commuters. That is hardly a success story. Portland transit riders would have been much better off if TriMet had continued to steadily improve bus service throughout the region rather than spend billions of dollars on rail service to a few narrow corridors.

My analysis also points out that the high cost of rail, including the cost of operating the new streetcar lines, resulted in deteriorating service and declining ridership in the early 2000s. Lewyn does not dispute this, but he insists on calling Portland’s transit policy a “success” because ridership grew after 1986. I’ve been accused of selectively using data, but in fact I look at all the data that are available, not just the data that support my preconceived notions.

Even if Portland’s transit ridership has grown since 1986, it has had an insignificant

effect on congestion and overall travel because it was so small to begin with. At

its maximum, light rail has never carried as much as 1 percent of Portland-

Lewyn concludes that the growth in Portland’s transit ridership disproves “the common claim that transit ridership will never grow anywhere because Americans are ‘wedded to their cars.’” But I never made that claim. Instead, I only argued that, if you want to increase ridership, rail is the wrong way to go because it costs too much and does too little. The rapid growth of Portland’s transit ridership when it was improving bus service and the slow growth (or decline) in ridership when it was building and operating rail prove this to be true.

As far as I know, rail transit is not one of the planks in the New Urbanist platform.

So it is puzzling that Lewyn feels the need to defend this expensive boondoggle.

While Portland’s light-

Congestion

Portland congestion is growing, and my paper shows that planners not only have done little to stop this growth, they are actively trying to encourage it. Lewyn responds by citing Texas Transportation Institute data to show that congestion in some other cities is growing at least as fast as in Portland.

Of course, if you suffer a recession and an 8 percent loss of jobs, as Portland did

in the early 2000s, traffic congestion is not going to grow very fast. Smart-

The various measures of congestion are pretty inexact anyway. But we know that certain

investments, such as traffic signal coordination, new highway capacity and congestion

pricing of roads, can reduce congestion. We know that other investments, such as

light-

Portland has opted for the measures that increase congestion and that cost a lot but do little. Portland planners predicted that their plan would quintuple the amount of time travelers waste in traffic in little more than two decades. Metro, Portland’s regional planning agency, has set a target of allowing congestion on most Portland freeways and arterials to increase to “level of service F” — a traffic engineering term meaning the worst possible congestion.

Metro opposes anything that would relieve congestion on these roads because, says Metro’s leading transportation planner, such relief “would eliminate transit ridership.” Whether Portland congestion is growing faster or slower than some other regions’ is not as important as the fact that Portland planners are deliberately making it worse.

Tomorrow I’ll focus on CNU’s comments on land-

1

Reprinted from The Antiplanner