No Light Rail in Vancouver!

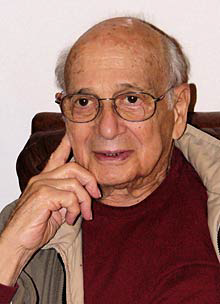

Many of things written in this blog in 2007 are mere echoes of statements made by Melvin Webber thirty to forty years ago. Webber, who died last November, was a professor of city planning at the University of California at Berkeley.

The latest issue of Access magazine, which Webber founded fifteen years ago, is a tribute to Webber, with articles by Martin Wachs, Robert Cervero, Peter Hall, Jonathan Richmond, and other researchers who are themselves legendary in the urban and transportation planning fields.

In these tributes, the adjective most often used to describe Webber is “skeptical.” “Mel’s deep skepticism was almost a charicature,” says Wachs. “He had the audacity to ask, over and over again, whether our most widely held beliefs could actually be supported by evidence.”

“I contend that we have been searching for the wrong grail, that the values associated with the desired urban structure do not reside in the spatial structure per se,” Webber wrote back in 1963. Modern communications and transportation technology rendered most planners’ idea of what a city should look like obsolete.

The title of the article was Order in Diversity: Community without Propinquity, and Webber’s lesson was that those who say we need certain kinds of urban designs to promote community are wrong.

Ten years later, Webber joined with another writer to criticize the theory of planning.

Planning problems “are ill-

In 1976, Webber took a close look at the then-

“If BART has achieved any sort of unquestionable success, it is as a public relations

enterprise,” Webber continued. “BART has projected a superb image from the start:

a high-

This sort of skepticism guided Webber throughout his career. As noted in the BART

paper, Webber believed that transit agencies should compete against the auto not

by using expensive, nineteenth-

Webber was an unabashed supporter, if not an enthusiast, of autos and sprawl. “Autos

are popular because the auto-

Webber was also skeptical of plans that tried to lock up every available acre of open space. “The task is not to ‘protect our natural heritage of open space’ just because it is natural, or a heritage, or open, or because we see ourselves as Galahads defending the good form against the evils of urban sprawl,” he wrote in the propinquity paper. “This is a mission of evangelists, not planners.”

Webber would almost be enough to restore my faith in planners. However, he himself was not educated as a planner; his training was in economics and sociology. As I’ve noted before, most planning schools (including the one at UC Berkeley) are associated with architecture schools. So the graduates of these schools end up focusing on urban design and aesthetics. Too few end up with Webber’s skepticism.

If you Access magazine in hard copy format, you can get a free subscription and/or order back issues at no charge.

11

Trackback • Posted in News commentary

The Skeptical Planning Professor

Reprinted from The Antiplanner