No Light Rail in Vancouver!

Prove It! #1. The Phony Problem of Sprawl

Russians say that Americans don’t have real problems, so they make them up. Urban

sprawl is one of those made-

Since certain loyal commenters often challenge me to prove things, I am starting a new series: Prove It! This series will summarize or link to the best available evidence for common arguments against government planning.

In response to a recent post, one of the Antiplanner’s loyal commenters asked me

to prove that the benefits of land-

Flickr photo by Craig L. Patterson.

Does sprawl threaten farm production?

According to the Department of Agriculture, the United States has more than 900 million acres of farmlands (crop lands, pasture lands, range lands), less than 40 percent of which are actually used for growing crops. To some degree, that 40 percent is the best of the 900 million acres, but to a large degree these lands are interchangeable and the area used for crops is the land that just happens to be close to sources of irrigation water, markets, or other farm needs.

The number of acres used for growing crops has declined in recent years, but that

is as much because per-

By comparison, only about 70 million acres are considered “urban” and 108 million are “developed” (including rural roads and rural developments covering more than a quarter acre). See these open space data for more details. (Some of the numbers are in square miles; multiply by 640 to get acres.)

The U.S. Department of Agriculture says urbanization is “not considered a threat to the Nation’s food production,” but it worries about farm “fragmentation.” However, European farms are much smaller and often more fragmented than ours, and they are just as productive.

Does sprawl threaten forests?

The U.S. has about 400 million acres of private forests and around 200 million acres more of public forests. Recent reductions in commercial forest acreage are more due to reclassification as wilderness than urbanization.

The automobile actually led to the recovery of about 80 million acres of commercial forests that had been in use as horsepasture. Another 40 million acres of horsepasture was converted to crop lands. So the auto has restored more forest and crop lands than sprawl has converted to urban development.

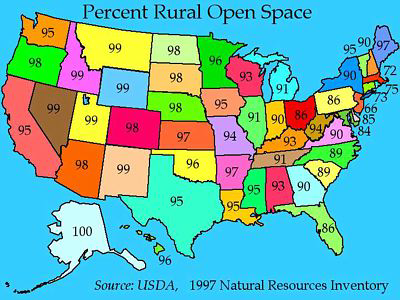

Does sprawl threaten open space?

The U.S. is about 95 percent rural open space (meaning densities lower than about

1,000 people per square mile, which is roughly equal to two-

Click to see a larger map.

Does sprawl force people to drive more?

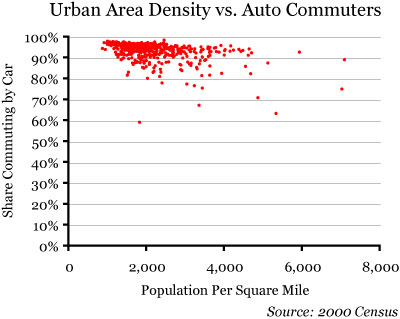

I’ve used these numbers before, but it is useful to review them again here. According to the 2000 census, Los Angeles is the densest urban area in the United States, and 89.5 percent of Los Angeles commuters usually drive to work. Just to the south, San Diego is only half as dense as L.A., and 90.9 percent of its commuters drive to work.

Atlanta is only half as dense as San Diego, and 93.5 percent of its commuters drive to work. And Lompoc California is about half as dense as Atlanta, and 94.4 percent of its commuters drive to work.

So doubling density might get a little more than 1 percent of commuters out of their cars. That’s not much. The chart below suggests that some other factors have more do with driving than density.

Click on the chart to download an Excel spreadsheet with 2000 census data for more than 400 urban areas showing densities and the share of commuters who take cars, transit, or walk/bike to work.

What are those factors? Most of the regions below 89 percent fall into one of two categories: Either they are university towns, where a high proportion of workers are young and they walk or bicycle to work; or they are older cities like New York that still have a very dense job center at their core.

Planners can’t do much about changing the age of their region’s population, but they

might try to force more employers to locate downtown. This, however, would make the

suburbs mad, so instead planners today focus on creating a “jobs-

Low densities, large parking lots, and other indicators of sprawl are effects of automotive technology. They don’t make people auto dependent; they enable people to be auto liberated. Density and various design features planners want to impose will have, at best, marginal effects on the amount of driving people do.

Does sprawl increase urban-

The Costs of Sprawl 2000 estimated that sprawl — low-

But let’s say that it is true. Is $11,000 per house really a problem when policies aimed at increasing urban densities increase housing costs by tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars per home? The appropriate way to deal with the $11,000 cost, if it is real, is to create a limited improvement district that can amortize the cost over, say, 30 years. The homeowners in that district would pay an assessment of about $75 a month for those thirty years. Unlike an impact fee, this would not increase the general price of housing in the area.

Does sprawl make people fat?

No; see my entry for Junk Science Week #3.

Does sprawl reduce people’s sense of community?

No; see my entry for Junk Science Week #1.

Conclusion

There may be other problems people have with sprawl that I haven’t addressed here. If so, I invite commenters to raise them. But these are the most common arguments against sprawl. If these arguments don’t hold water, then efforts to curb sprawl will produce few benefits — and if those efforts have a significant cost, then that cost is likely to be much larger than any benefits.

17

Trackback • Posted in Mission, Regional planning

Reprinted from The Antiplanner