No Light Rail in Vancouver!

This was in the middle of the New Deal and planning was all the rage. Oregon even

had a State Planning Board, which viewed this disaster as a great opportunity to

demonstrate the benefits of sound land-

The board then gave Harry Freeman, a Portland planning consultant, a free hand to plan a completely new town. After the plan was approved, former landowners would be allotted properties of comparable worth to the ones they had put into the pool.

In March, 1937, Freeman presented his plan to the town. Freeman said that the previous

arrangement of homes and businesses was “uneconomic” because they were so “scattered”

across the landscape. In other words, the town’s density was too low because people

didn’t build on adjacent lots but often left many lots vacant between homes. The

planner considered it “obvious” that such “haphazard development” imposed higher

costs “than in a reasonably compact, well-

Green is open space, yellow residential, red industrial, and blue retail/commercial/government;

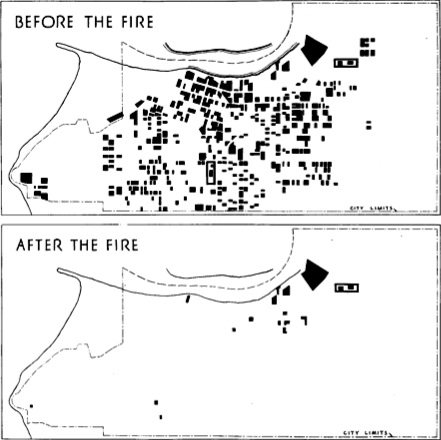

the solid red line is Highway 101. Prior to the fire, homes were scattered in many

of the open spaces, while the cross-

Accordingly, Freeman’s plan called for a much more compact development with 450 homes

located on quarter-

The plan called for many other changes as well. In 1936, the town’s business district was located along the Coquille River, reflecting the town’s history as a major port. Freeman moved commercial businesses a mile south, while leaving industrial businesses on the river. The former commercial area was turned into a residential area. All buildings in the business district were to be built to a similar architectural style.

By 1936, Bandon was connected to the rest of the state by U.S. Highway 101, which went through town on ordinary city streets. The highway intersected at least seventeen streets in its journey through Bandon. Freeman proposed to turn 101 into what he called a “traffic ‘freeway’ through the city,” with only six connections to other streets. To maintain the beauty of this freeway, no private land would front on the highway.

In another effort to preserve scenic beauty, all waterfront property would be left in the public domain. While many lots would have ocean and river views, Freeman’s drawings show most of those views obscured by rows of trees planted in front of every major street — but that just may be an drafting convention.

“The greatest danger ahead in the rebuilding of Bandon is in possible deviation from

the town plan,” Freeman immodestly claimed. “No leeway should be granted any individual

to allow a variance or approve any change, minor or otherwise, from the plan. Likewise,

no non-

When Freeman’s plan was presented to the public, the local newspaper urged everyone to “forget any selfish aims he might have and work together for the common good.” In a report submitted to the state in November, 1937, Freeman claimed that 300 Bandon property owners unanimously approved the plan at the March, 1937, meeting.

Yet the plan was never implemented. Though Freeman worked fast to produce a plan in just five months, builders worked faster and many homes and businesses had been rebuilt within a month of the fire. Building permits were supposed to be for only one year, yet many of those buildings remain today. This includes Bandon’s city hall, which was used as such for thirty years and has now been turned into the museum where I found Freeman’s report.

Apparently, local enthusiasm for the plan waned by mid-

Bandon today as seen by Google Earth; the red line marks the approximate outline of the above map. The area that Freeman proposed be the commercial center of town is dedicated to schools. Many businesses remained in the original commercial area on the Coquille River waterfront, while others line highway 101. Homes spread out at the comfortable low densities. The green spaces are all still there, but most of them are called “backyards.” Click on the photo for a larger version.

Today, Bandon old timers lament the town’s failure to build a model city. Bandon’s

unofficial historian, Dow Beckham, wrote that if the plan had been followed, “city

planners would likely have journeyed to the area to take pictures and notes of how

the job was accomplished.” But even without the plan, “today’s Bandon is unique and

has a special appeal to tourists and retirees. Who knows whether well-

In fact, it is clear that Freeman’s plan would have been much worse than the Bandon that exists today. First, Freeman did not expect the town’s numbers to grow, so he planned for a stagnant population. Today’s population of 3,100 is more than twice as great as that of 1937, and nearly all of the new people would have been forced outside of the plan’s limits.

Second, the idea of turning 101 into a freeway, with no private businesses fronting

on the road, would have lost Bandon an enormous amount of its tourist business. Most

people would have driven through and never seen the town. In 1937, tourism was a

distant fourth after timber, agriculture, and fishing, but today it is the city’s

leading industry. Without tourism, Bandon today would probably not even support the

1,500 people who lived in it in 1936 (making Freeman’s first error a self-

Third, Freeman’s plan to separate the commercial and industrial parts of town, which were adjacent to one another in 1936, ignores important synergies between these two areas. The increased cost of moving between the two would have imposed even higher barriers to the fishing and timber industries that are barely hanging on today.

Fourth, the plan to make all waterfront land public would have destroyed an important

attraction to potential residents of Bandon. Today, ocean-

I would roughly estimate that 10 to 20 percent of Bandon’s ocean-

Finally, Freeman’s basic premise — that it is “inefficient” and wasteful to not force people to build on adjacent lots — has not been proven by time. Despite the higher population, Bandon’s population density today is lower than it was in 1936. Numerous lots and blocks remain vacant as most people choose to live near the water or in splendid isolation from everyone else. While Bandon has suffered from declines in fish and timber supplies, there is no indication that it has suffered from low densities. Indeed, higher densities might have made it unattractive to people who wanted to get away from crowded urban areas.

The idea of getting private landowners to pool their property and let planners decide how it should be used must have seemed awesome in 1936. Today it feels faintly communistic. Unfortunately, planners in Oregon today have almost as much power even without property pools.

After Katrina damaged much of New Orleans and nearby areas, planners proposed that the region be rebuilt following New Urban principles. I wonder how many planners today are salivating at the chance to plan the reconstruction of Greensburg, Kansas.

2

Trackback • Posted in City planning

Anti-

The near-

Reprinted from The Antiplanner